Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos, Sr.

1975-1986

SIGNIFICANT EVENTS

LIST OF OFFICIALS

Chairperson: Imelda Romualdez-Marcos

Vice Chairperson: Irene R. Cortez

Executive Director: Dr. Leticia P. de Guzman

Commissioners:

Dep.PM Jose A. Roño

Acting Min. Pacifico Castro

Min. Blas F. Ople

Min. Roberto V. Ongpin

MP Helena Z. Benitez

Amb. Leticia R. Shahani

Amb. Rosario G. Manalo

Mayor Adlina S. Rodriguez

Dr. Gloria T. Aragon

Dr. Belen E. Gutierrez

Dr. Lucrecia R. Kasilag

Dr. Minerva G. Laudicio

Carmen G. Nakpil

Sylvia M. Ordoñez

Nora Z. Petines

Santanina T. Razul

Jovito A. Rivera

Atty. Carolina B. salazar

Dr. Mona D. Valisno

The creation of the National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women (NCRFW) can be traced back to the 1960s.1 It was facilitated by intense lobbying of women non-government organizations under a national organization called Civic Assembly of Women of the Philippines (now called National Council of Women of the Philippines), a group with 210 affiliated women organizations nationwide.2

The NCRFW was founded by Leticia Ramos Shahani, who became the Commission’s Chairperson later.3 Shahani was the author of landmark laws such as the Strengthening the Prohibition of Discrimination Against Women in the Workplace, the Anti-Rape Law of 1997, and the Rape Victim Assistance and Protection Act of 1998.4

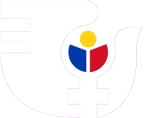

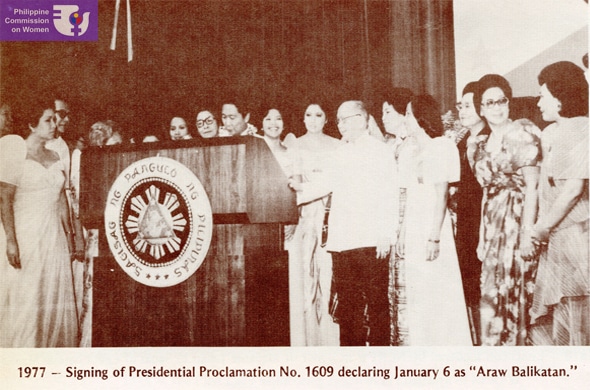

Established on January 7, 1975, during the International Women’s Year, President Ferdinand E. Marcos signed Presidential Decree No. 633. He instituted the NCRFW—a body that ensured the full integration of women for economic, social, and cultural development. It was the first national women’s machinery established in Asia.5

The NCRFW was the response of the Philippine government to the UN General Assembly’s call for member countries to establish government machinery to attend to women’s concerns.6

Mandated to “review, evaluate, recommend measures, including priorities to ensure the full integration of women for economic, social and cultural development at the national, regional and international levels and to ensure further equality between women and men,” its Board of Commissioners was composed of Cabinet Secretaries of government Departments tasked to implement policies and programs on women’s advancement, and NGOs representing various sectors.7

The first Board of Commissioners was chaired by then First Lady Imelda Romualdez Marcos, with the late Justice Irene Cortez as Vice-Chairperson. Dr. Leticia Perez de Guzman, former President of the Philippine Women’s University (established as the first women’s university in Asia founded by Asians), was its first Executive Director.8

NCRFW’s work during its first decade was influenced by the Women and Development framework vis-à-vis the UN Global Program for Action. It focused on improving women’s welfare and on programs and projects for women being left out of development on account of their lack of education, training, credit, and low self-esteem.9

The Commission mobilized the Balikatan sa Kaunlaran, a nationwide women’s movement organized to create opportunities for expanded roles of women in the nation’s economic, social, and political activities. They mobilized women leaders in villages, cities, municipalities, and provinces. They involved them in programs and projects that could improve women’s participation, leadership, livelihood, and income generation skills to augment the family income.10

Focused on health and nutrition to community cleanliness, food production, education, and literacy, Balikatan’s claimed membership was close to 3 million, organized into around 132 provincial and city councils.

Balikatan was subsequently incorporated as a non-profit organization, the National Balikatan Foundation, which continued to pursue its mission of providing direct assistance to economic and social undertakings of women for entrepreneurial development.11

Remedios Rikken attended the Women’s Conference in Mexico from June 19 to July 2, 1975. It was the first international conference held by the United Nations focusing on women’s issues but led by a man. According to NCRFW’s Former Chairperson Leticia Ramos-Shahani, “For the first time, governments met to discuss women’s issues at the highest levels. Women got together—north and south, rich and poor.” 12

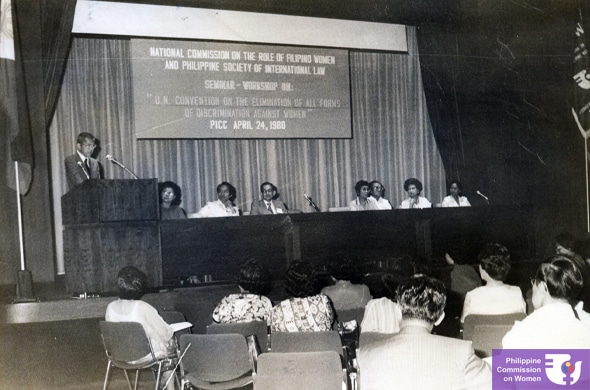

The United Nations adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) or the International Bill of Rights of Women in 1979 and took effect on September 3, 1981. It established a framework that drew on three over-arching principles: equality in opportunity, equality in access and equality in results.13 Shahani led the drafting of this bill.14

NCRFW’s initiatives also focused on conducting policy studies and lobbying for the issuance of executive and legislative measures concerning women; establishing a clearing house and information center on women; and ratifying of the UN CEDAW.

LEGISLATIVE VICTORY

Presidential Decree 633: Creation of the NCRFW

1985

SIGNIFICANT EVENT

Executive Director Remedios Rikken attended the Women’s Conference in Nairobi, Kenya, where she became acquainted with “gender mainstreaming.” The Nairobi Conference laid out a plan of action until 2000 on a broader range of issues, including a new focus on gender-based violence. 15

Cited Sources:

1 Honculada, J. and Ofreneo, R. (2018.) The National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women, the women’s movement and gender mainstreaming in the Philippines. Retrieved here.

2 NCRFW. (2001). Making Government Work for Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality. Retrieved here.

3 Jett, Jennifer. (2018). The New York Times. “Overlooked No More: Leticia Ramos Shahani, a Philippine Women’s Rights Pioneer.” Retrieved here.

4Alporha, Veronica, Evangelista, Meggan and Hega, Mylene. (2017). “Feminism and the Women’s Movement in the Philippines.” Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Retrieved here.

5 NCRFW. (2001). Making Government Work for Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality. Retrieved here.

6 Maniquis, Estrella Miranda. (July 1990). “Gender Equality May Become a Way of Life for Filipinos.” ‘Mare Magazine. Vol. 2. No.1.

7 NCRFW. (2001). Making Government Work for Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality. Retrieved here.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Jett, Jennifer. (2018). The New York Times. “Overlooked No More: Leticia Ramos Shahani, a Philippine Women’s Rights Pioneer.” Retrieved here .

13 PCW. N.d. “What is CEDAW?” Retrieved here.

14 Jett, Jennifer. (2018). The New York Times. “Overlooked No More: Leticia Ramos Shahani, a Philippine Women’s Rights Pioneer.” Retrieved here.

15 Ibid.