Education Sector

Education improves the quality of life by enabling literate people to promote health, expand access to paid employment, increase productivity in market and non-market work, and facilitate social and political participation. As such, it is a basic human right that should be equally accessible to all.

The types of education offered in this country are classified into three: Basic Education, Middle Education or Technical and Vocational Education and Training and Higher Education. There have been recent changes in the Philippine Education System because of the passage of the Republic Act 10533 or the Enhanced Basic Education Act of 2013, which necessitates a coordinated and holistic approach to education due to the introduction of the K to 12 Program. K to 12 is a program that covers kindergarten and 12 years of basic education to provide adequate time for skills and concepts proficiency, develop lifelong learners, and prepare students for tertiary education.

In recent research 28 million Filipinos 1 are enrolled nationwide in public and private educational institutions from academic year 2016-2017 alone. This means that students, whether in basic, middle or higher education, comprise to around 27% of the entire population of the Philippines in the given year.

The Implementing Rules and Regulation of the Republic Act No. 10931, known as the ‘Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act of 2017’ was enacted to subsidize free tuition and other school fees in state universities and colleges, local universities and colleges and state-run technical-vocational institutions.

For the academic year 2018-2019, the subsidy benefited 655,083 women and 477,897 men. Of the 655,083 women, 28.37% or 185,874 are graduating while 8.87% or 58,125 are in their 3rd year.2 In addition, 8,057 of these women are categorized under persons with disability, in which they get another 50% of the annual benefit in addition to the regular allocation. Further, national government efforts to increase women’s access to retention and completion of education in technical and vocational education and training have been undertaken through TESDA scholarship program which caters and responds to challenges faced by women and girls in various poor communities. Based on TESDA’s report, these programs have produced a total of 1,733,646 graduates from 2014-2018.

Why prioritize this sector?

Educating women is imperative because it enables women to participate in the labor force and allows them to sustain herself and the needs of her family. This stems from the fact that in modern Filipino families, both husband and wife should engage in productive work to earn enough for their family’s needs.

Education has been a facilitating factor towards women’s economic empowerment. A mother’s level of education has been found to create positive educational outcomes for her children since she is primarily assigned in rearing of children. Educated women build smaller families, with lower rate of children dying in infancy; hence, surviving children are given better access to education. Furthermore, educated mothers lead a better quality life for their children.

YOUNG WOMEN AND GIRLS EDUCATION DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global health crisis, and this extreme occurrence appears to be affecting societies across the world. As of December 15, 2020, almost 73 million people have been infected, and over 1.6 million have died. In the Philippines, this translates into practically 450,733 infected and 8,757 deaths.3 This data shows that no one is exempted regardless of nationality, educational level, status, or gender. Thus, the Philippine government has taken some protective measures to prevent the spread of the virus by imposing community lockdown and cancellation of classes at all levels nationwide.

Hence, education is one of the sectors that was greatly affected. According to UNESCO, more than 1.2 billion learners have been affected around the globe and among this number are over 28 million Filipino learners across academic levels have to stay at home to prevent COVID-19 transmission.4

In March 2020, face-to-face education was canceled for several months. To cushion the losses in learning caused by the pandemic and to facilitate the continuity of education for all, the new normal delivery mode has been adopted by the Department of Education (DepEd), Commission on Higher Education (CHED), and Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TESDA). Although the learners, teachers, and other key education players were not prepared for a different educational experience, they adjusted to the new situation.

Education Before and During the Pandemic

Even before the pandemic, gender inequalities in education already exist. Access to education remains unequal because of persisting marginalization and poverty. And now that we have a low physical interaction in learning, that crisis may deepen and create a tremendous impact on the education system.

While school closures appear to be a reasonable solution, the long-drawn-out closure of schools and the abrupt transition to the new learning scheme may substantially affect learners, especially young women’s and girls’ unique situation, teachers, and parents. The COVID-19 shock brought anxiety and stress. Also, learning opportunities at home are limited because of economic burdens and distractions. In addition, parents play a critical role in their children’s education. The shift of responsibility in learning facilitation requires active participation to guide online distance learning. Parents may also face prolonged childcare, which eventually is delegated to their daughters.

Emerging Gender Issues in Education

Young women and girls reduced educational access and retention

According to UNESCO, school closures have sent about 90% of all students out of school, among them more than 800 million girls.5 Young women and girls are recognized as one of the vulnerable groups in the COVID-19 pandemic.

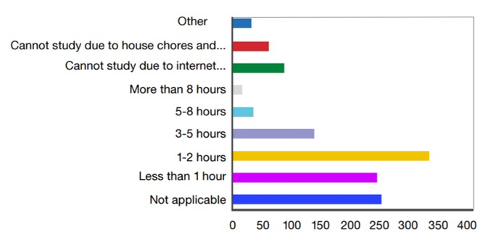

A survey conducted by Plan International among young women and girls found that inability to study at home has two leading causes: (1) internet connectivity problems and (2) the need to help with household chores.6

The internet connectivity problems can be associated with the socioeconomic status of the learner because not all have a distance learning device and capacity to connectivity. The economic recession caused by the pandemic worsened the financial realities of every family. They now have fewer resources and lower disposable income. Based on United Nations, some 23.8 million additional children and youth from pre-primary to tertiary may drop out or not have access to school next year due to the pandemic’s economic impact alone.7 Therefore, learners, particularly young women and girls, may consider delaying their education and taking some time off their studies.

Further, as young women and girls stay at home, they are delegated with more household chores, including childcare, which lessens their time for learning. This might also encourage parents, particularly those putting a lower value on girls’ education, to keep their daughters at home even after schools reopen.8 According to Plan International’s online survey, slim chances of returning to school are among the top concerns of young women and girls (Plan International).

As shown below in Figure 1: Time Spent Studying, there is a substantial reduction in the number of hours spent daily on studying by young women and girls. Among the respondents, 28% studied for one to two hours, while 20% studied for less than an hour; and only around 12% studied between three to five hours a day.9

Prevalence of gender biases and stereotypes embedded in curricula, instructional materials, learning media, textbook illustrations, and other educational materials and school policies, particularly in basic education

Now that we have shifted in digital learning, gender bias and stereotypes in curricula and learning materials are becoming more prevalent in printed materials and on different learning modalities. New instructional and teaching materials have not been thoroughly reviewed, thus containing some inaccuracy and inappropriateness in content and language. The prevalence of gender biases, stereotypes, and sexist languages embedded in curricula, instructional materials, and education policies poses a significant concern. The learning materials are the visible manifestation of the curriculum that conveys messages and shapes the mindset and perspective of the children. If constantly exposed, children will grow up with learned biases and stereotypes that will be very difficult to unlearn. This scenario may potentially destroy the learner’s intellectual curiosity. Hence, curriculum developers should be equipped and sensitized, whether in basic, higher education, and technical and vocational education and training (TVET).

Emergency Response in Education

All key implementing agencies in the education sector adopted the Learning Continuity Plan (LCP) to ensure continuity in education, inclusion, and education for all. The emergency response used was blended and flexible learning to avoid and limit the risks of infection in the academe.

In basic education, DepEd is keen on continuing education to give hope and make sure learners are still connected with the education spirit. Hence, DepEd adopted the Basic Education-Learning Continuity Plan (BE-LCP) to respond to basic education challenges brought about by COVID-19. The agency’s response plan is also embodied under Sulong EduKalidad. Multiple learning modalities and platforms were developed to ensure learning continuity, including digital online and offline, television, radio, and printed materials. Learning Resources and Platforms Committee was also created to guarantee that appropriate learning resources of good quality are made available and that the necessary platforms are engaged.10

To continue teaching and learning in higher education, CHED implemented a developmental project to assist institutions, teachers, and students in the transition to flexible learning. Flexible learning was done in three approaches: online learning or blended learning technology; macro and micro approach, a combination of online and offline activities; and the self-instructional modules / mostly offline activities.11

In addition, part of CHED’s initiatives to ensure effective teaching and learning outcomes include:

- provision of support services through capacity building training;

- continuous enrichment of the PHL CHED Connect,12 which contains higher education course materials in text, audio, video, and other digital contents that can be used for teaching, learning, and research purposes;

- grant of financial support/awards for research and materials development.

However, Operational Plan (OPLan) TESDA Abot Lahat: TVET Towards the New Normal is the emergency response of TVET for innovative solutions during the pandemic.13 They also have flexible learning delivery arrangements that Technical Vocational Institutions (TVIs) can adopt, such as:

- Face-to-face Learning

- Online Learning

- Blended Learning

- Distance Learning

However, these are subject to evaluation depending on the capacity of the TVI to implement their preferred mode.

In 2020, TESDA Online Program (TOP) became more active and widespread.14 It was developed to provide free courses for all who would like to acquire new skills in the convenience of their own homes, mobile phones, and computers. Moreover, to effectively implement training programs, upskilling and reskilling of learning facilitators and trainers, including online and blended learning delivery, were given priority. TESDA also provided a mandatory enrollment of all TESDA employees and trainees to the eLearning titled: “Practicing COVID-19 Preventive Measure in the Workplace”.15

References and Cited Sources:

1 Estimate figure based from the data gathered from CHED, TESDA, and Rappler for year 2017. Rappler was cited due to absence of online data from DepEd.

2 Beijing Platform for Action +25 (2019). CHED inputs.

3 Worldometer, 2020. Accessed here on February 7, 2022.

4 Giannini, Stefania. “Covid-19 School Closures Around the World Will Hit Girls Hardest.” UNESCO. Retrieved here on March 2022.

5 Muller, James and David, Nathan. Gendered Effects of School Closures during the Covid-19 Pandemic. The Lancet. Reterieved here on February 7, 2022.

6 Through Her Lens: The Impact of COVI-19 on Filipino girls and young women. Plan International. Retrieved here on February 7, 2022.

7 Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. United Nations. Retrieved here on February 7, 2022.

8 Muller, James and David, Nathan. Gendered Effects of School Closures during the Covid-19 Pandemic. The Lancet. Reterieved here on February 7, 2022.

9 Through Her Lens: The Impact of COVI-19 on Filipino girls and young women. Plan International. Accesed here on February 7, 2022.

10 Department of Education. The Basic education Learning Continuity Plan in Time of COVID-19. June 19, 2020. Retrieved here on February 7, 2022.

11 CHED Memorandum Order No. 4 Series of 2020: Guidelines on the Implementation of Flexible Learning. Retrieved here on February 7, 2022.

12 PHL CHED Connect. 2020. Accessed here on February 7, 2022.

13 TESDA Circular: TESDA’s Implementing Guidelines on TVET arrangements Towards the New Normal. May 29, 2020. Retrieved here on February 7, 2022.

14 TESDA Online Program. Accessed here on February 7, 2022.

15 TESDA Memorandum Circular No. 214-2020.