Maria Corazon Cojuanco Aquino

1986

SIGNIFICANT EVENTS

The NCRFW’s leadership was primarily drawn from academia and women’s non-governmental organization, and its significant themes resonate with issues raised by the women’s government. With its doors opened to the vast array of women’s organizations, the new Board of Commissioners in 1986 included women’s advocates, feminists, and women professionals representing the private sector. The deepest hues of purple, the symbolic color of feminism, glistened in the NCRFW.1

LIST OF OFFICIALS

Chairperson: Sen Leticia Ramos-Shahani (1986-1987)

Dr. Patricia B. Licuanan (1987-1992)

Executive Director: Remedios I. Rikken

Government Organization Commissioners

Sec. Carmencita Reodica, DOH

Dir. Fe Agudo-Hidalgo, DECS

Sec. Nieves R. Confessor, DOLE

Sec. Corazon Alma de Leon, DSWD

Dir. Lilia R. Bautista, DTI

Fe D. Laysa, DA

Carolina delos Santos-Guina, NEDA

Non-Government Organization Commissioners

Rita G. Andaya

Gloria T. Aragon

Aminah Rasul Bernardo

Corazon de la Paz

Alicia Semplo-Diy

Trinidad A. Gomez

Jurgette Honculada

Leonor I. Luciano

Ma. Lourdes V. Mastura

Imelda M. Nicolas

Sonja A.H. Rodriguez

Carmen Enverga-Santos

Zorayda Tamano

Esther A. Vibal

The Board of Commissioners was chaired by Foreign Affairs Undersecretary Leticia Ramos Shahani, who ran for Senate in 1987 and turned over her post to Dr. Patricia Benetiz Licuanan. Dr. Licuanan and Executive Director Remedios Ignacio Rikken broke new ground in making women’s issues a collective concern of many government and non-government organizations.2

The change in government has also altered the composition of the NCRFW officials. They reviewed the Commission’s mandate and decided to focus on the Commission’s activities on mainstreaming women’s concerns in policymaking, planning, and programming of all government agencies.3

Patricia “Tatti” Licuanan, who served as NCRFW Board Chair most of President Corazon C. Aquino’s presidency, described this period as the “best of times [and] worst of times.” She said that the time was favorable because the national leadership was “deeply committed to reform” and was “comfortable with non-government organizations and government organizations eager to work with them.” Even if President Aquino was not a feminist, she instinctively supported women’s causes. However, it was also the worst of times for women’s problems which could quickly be sidelined with an economy near shambles.4

During her presidency, spaces were opened for the women’s movements to grow and allow for progressive participation of women at different levels of society. 5

The women’s movements campaigned for gender equality provisions in the new Constitution that the Constitutional Commission drafted. The President appointed the Constitutional Commission after being put into power on the strength of the EDSA revolt against President Ferdinand E. Marcos. Four organizations met to consolidate proposals: the Concerned Women of the Philippines, Women’s Caucus, GABRIELA, and Lakas ng Kababaihan spearheaded by PILIPINA.6 The proposals encompassed the following: seeking women’s fundamental equality with men in all spheres of life; affording protection to working women, including a concern for child care; and ensuring equal work and pay; recognizing the economic value of housework; safeguarding women’s choice of career and property rights, and mandating women’s equal representation in policymaking at all levels. 7

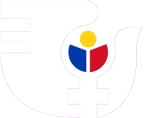

During the Women’s Day of Unity in July 1986, the outgoing NCRFW Executive Director Leticia de Guzman presided over the signing of the final document to be handed over and presented to the Constitutional Commission President Cecilia Muñoz-Palma. There were 2000 representatives from 200 women’s organizations and school and government delegations affixed their signatures to the document that sought to include gender equality in the Philippine Constitution.8

Women’s concerns were positioned at the heart of the government agenda and under gender and development (GAD) mainstreaming strategy. All government entities were responsible for addressing gender issues in their policies, programs, and projects. The battle cry was to make the government work for women toward a society where women and men equally contribute to and benefit from development.9

Established a clearinghouse and information center on women, a national databank on women that served as the basis for policy formulation.10

Produced information materials for the United Nations conference in Nairobi dealing with topics such as stereotyping, women in science and technology, values of rural women, and women in export processing zones.11

1987

SIGNIFICANT EVENTS

Integration of gender equality on 1987 Philippine Constitution.

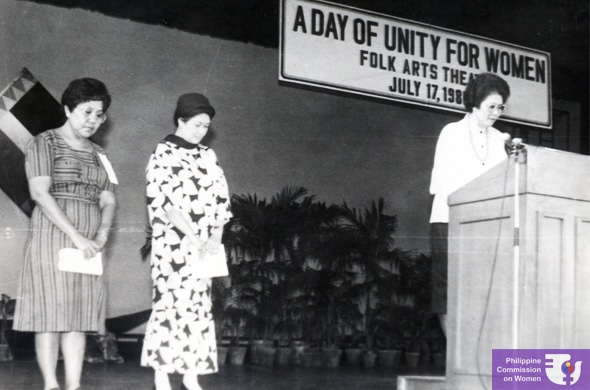

The NCRFW held various consultation workshops among different women’s groups that resulted in the crafting of the Philippine Development Plan for Women (PDPW) 1989-1992, which became a companion volume to the Medium-Term Philippine Development Plan (MTPDP) 1987-1992. The PDPW served as the government’s blueprint for integrating women into the development processes.12

The single statement in the MTPDP: “Women, who constitute half of the nation’s population, shall be effectively mobilized” has originated the PDPW.13

The National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) provided essential support not only in integrating portions of the PDPW into the 1990-1992 update of the MTPDP, but it also included the NCRFW in various development planning sub-committees as well as in mainstreaming the Country Program for Women through various mechanisms that expanded access to resources.14

The formulation and subsequent adoption of the PDPW and the broader efforts to mainstream gender in government were championed by several feminist officials in the Aquino administration: Executive Director Remedios Rikken, NEDA Director-General, and Economic Planning Secretary Solita Monsod, NCRFW Commissioner for Labor Jurgette Honculada and NCRFW Chair Patricia Licuanan (who succeeded Leticia Ramos-Shahani after she got elected to the Senate in 1987).15

NCRFW’s tasks to implement the PDPW were as follows :

• Strengthen the database on women to enable monitoring of the status of women through time and the impact of policies and programs on women

• Establish appropriate institutional mechanisms in government

• Massive gender consciousness-raising and training for gender-responsive planning

• Technical assistance in policymaking and programming for women’s development

LEGISLATIVE VICTORIES

The 1987 Philippine Constitution mandates that the State “recognizes the role of women in nation-building and ensure the fundamental equality before the law of women and men” (Art. 11, Sec 14) and recognizes women’s maternal and economic role (Art XIII, Sec. 14), and women’s special health needs (Art. XIII, Sec. 11), and allows Filipino women married to aliens to retain their citizenship if they chose to do so (Art. IV).

Not long after the ratification of the Constitution, President Aquino issued Executive Order 227 or The New Family Code of the Philippines, which eliminated many of the discriminatory provisions in the Civil Code of the Philippines that had been based on Spanish colonial law.16

1988

LEGISLATIVE VICTORIES

Proclamation No. 224: Declaring the 1st week of March as Women’s Week, with March 8 as Women’s Rights and International Peace Day

Proclamation 227: Observance on the month of March as “Women’s Role in History Month.”

1989

SIGNIFICANT EVENTS

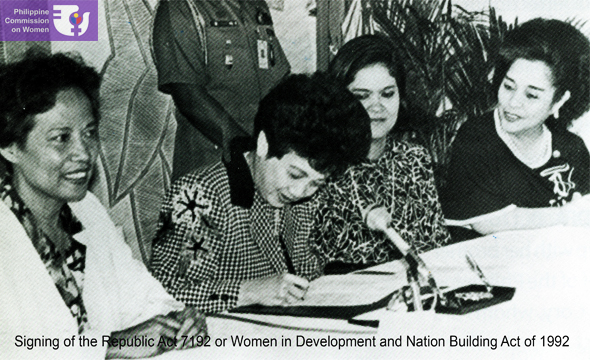

The growing concern to improve the conditions of women during the Aquino administration resulted in the enactment of necessary laws.17

The NCRFW in coordination with NEDA monitored the implementation of the PDPW by various government agencies.18 Upon consultation with President Aquino, the NCRFW was authorized to issue orders, circulars, or guidelines as may be necessary for the implementation, coordination, and monitoring of the PDPW.19 The governmental organization and nongovernmental organization partnership was nurtured early on by the NCRFW through a Congress in 1989.20

Women ventured into non-traditional jobs. Sponsored by the Netherlands government, the Women in Non-Traditional Trades Project was the approach to women’s development that offered free training to nine basic trades: automotive, electricity, carpentry, furniture and cabinet making, refrigeration and air-conditioning, masonry, plumbing, welding and repair and maintenance of office equipment.21

LEGISLATIVE VICTORIES

RA 6725: An Act Strengthening the Prohibition on Discrimination Against Women with Respect to Terms and Conditions of Employment

Executive Order 348: Approval and Adoption of Philippine Development Plan for Women

1990

SIGNIFICANT EVENTS

It was only in the Philippines when the celebration of International Women’s Day was filled with hundreds of activities yearly in Metro Manila and provinces, engaging both NGO women and sister’s organizations in government. The prolonged observance highlighted women’s culture and aided in the full flowering of women’s advocacy.22

“Gender equality” became part not only in the vocabulary of Filipinos in government but also in their way of thinking and performing. Gender-sensitive and gender-responsive development planning and programming have been institutionalized in the Philippine government. It was one of the principal mechanisms identified in the Philippine Development Plan for Women (1989-1992).23

The NCRFW conducted a gender analysis of Philippine Laws to encourage the legislature to remove discriminatory provisions in our laws.24

LEGISLATIVE VICTORIES

RA 6949: An Act to Declare March Eight of Every Year as A Working Special Holiday to Be Known as National Women’s Day

RA 6955: Anti-Mail Order Bride Law that outlaws the practice of matching Filipino women for marriage to foreign nationals on a mail-order basis

RA 6972: Barangay-Level Total Development and Protection of Children Act that mandates the establishment of day care centers in every barangay

1991

SIGNIFICANT EVENTS

Government officials and staff were capacitated with skills to make gender and development concerns a way of life in the government. This campaign was supported by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) under Phase I of the Institutional Strengthening Project from 1991 to 1996.25

Gender mainstreaming was part of President Aquino’s legacy to the incoming administration of President Fidel V. Ramos. Towards the end of her term, gender mainstreaming lay with government structures.26

The role of non-government organizations was crucial, especially when gender mainstreaming started moving out to pilot regions and local government units.27 Community-based NGOs and people’s organizations played significant roles that enabled empowerment for women in the communities and articulated their interests in various levels of decision-making.28

The Ugnayan ng Kababaihan sa Pulitika drafted a ten-point women’s agenda with demands related to peace, the environment, agriculture, work, business and industry, health, social services, education, culture and media, violence against women, and political participation. Among the presidential candidates, only Fidel V. Ramos signed the agenda.29

LEGISLATIVE VICTORY

RA 7160: Local Government Code of 1991 which introduced a mechanism for women’s participation at the local government level

No Specific Year

SIGNIFICANT EVENTS

Established Focal Points for Women, promoted data disaggregation by sex, built a trainer’s pool and developed a critical mass of gender advocates within the bureaucracy.30

The Aquino administration opened the Philippine Military Academy to women. Female cadets showed commendable performance, with one of them topping the graduating class in 1999.31

Introduced gender-responsive measures in government such as flexi-time, daycare, career advancement for women in government, and equality advocates.32

Cited Sources:

1 NCRFW. (2001). Making Government Work for Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality. Retrieved here.

2 Honculada, J. and Ofreneo, R. (2018.) The National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women, the women’s movement and gender mainstreaming in the Philippines. Retrieved here on June 2019.

3 Philippine Commission on Women. (n.d.). Herstory. Retrieved here on June 2019.

4 Honculada, J. and Ofreneo, R. (2018.) The National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women, the women’s movement and gender mainstreaming in the Philippines. Retrieved here on June 2019.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 NCRFW. (2001). Making Government Work for Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality. Retrieved here.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Alporha, Veronica, Evangelista, Meggan and Hega, Mylene. (2017). Feminism and the Women’s Movement in the Philippines. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Retrieved here on June 2019.

13 National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women. (n.d.) as cited in Alporha, Veronica, Evangelista, Meggan and Hega, Mylene. 2017. Feminism and the Women’s Movement in the Philippines. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Retrieved here on June 2019.

14 National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women. (n.d.). as cited in Alporha, Veronica, Evangelista, Meggan and Hega, Mylene. 2017. Feminism and the Women’s Movement in the Philippines. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Retrieved here on June 2019.

15 Alporha, Veronica, Evangelista, Meggan and Hega, Mylene. (2017). Feminism and the Women’s Movement in the Philippines. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Retrieved here on June 2019.

16 Maniquis, Estrella Miranda. (1990, July). Gender Equality May Become a Way of Life for Filipinos. ‘Mare Magazine. Vol. 2. No.1. Retrieved here

17 Alporha, Veronica, Evangelista, Meggan and Hega, Mylene. (2017). Feminism and the Women’s Movement in the Philippines. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Retrieved here on June 2019.

18 Ibid.

19 Executive Order 348. (1989). Retrieved here on July 2019.

20 Ibid.

21 Honculada, J. and Ofreneo, R. (2018.) The National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women, the women’s movement and gender mainstreaming in the Philippines. Retrieved here on June 2019.

22 Maniquis, Estrella Miranda. (1990, July). Gender Equality May Become a Way of Life for Filipinos. ‘Mare Magazine. Vol. 2. No.1. Retrieved here.

23 Honculada, J. and Ofreneo, R. (2018.) The National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women, the women’s movement and gender mainstreaming in the Philippines. Retrieved here on June 2019.

24 Maniquis, Estrella Miranda. (1990, July). Gender Equality May Become a Way of Life for Filipinos. ‘Mare Magazine. Vol. 2. No.1. Retrieved here

25 Ibid.

26 NCRFW. (2001). Making Government Work for Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equality. Retrieved here.

27 Honculada, J. and Ofreneo, R. (2018.) The National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women, the women’s movement and gender mainstreaming in the Philippines. Retrieved here on June 2019.

28 Ibid.

29 Alporha, Veronica, Evangelista, Meggan and Hega, Mylene. (2017). Feminism and the Women’s Movement in the Philippines. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Retrieved here on June 2019.

30 Honculada, J. and Ofreneo, R. (2018.) The National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women, the women’s movement and gender mainstreaming in the Philippines. Retrieved here on June 2019.

30 National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women. (2001). Making Government Work for Gender Equality.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.